The Contract with Myself

Short Story. "I saw my replacement through the window."

When I felt everything was in danger, that my life hung by a thread because of a serious health issue—as serious as health problems can be these days; a matter of ego, as some philosophers say—I signed the contract. In Riviera’s offices, with ash-gray walls and a faint, languid light, pale almost like my skin, I read the clauses, scrawled my signature, and transferred the payment for the service. It was all my money: savings built up over years, plus the little that remained of my parents’ inheritance. They had never been able to access a replacement, but I could.

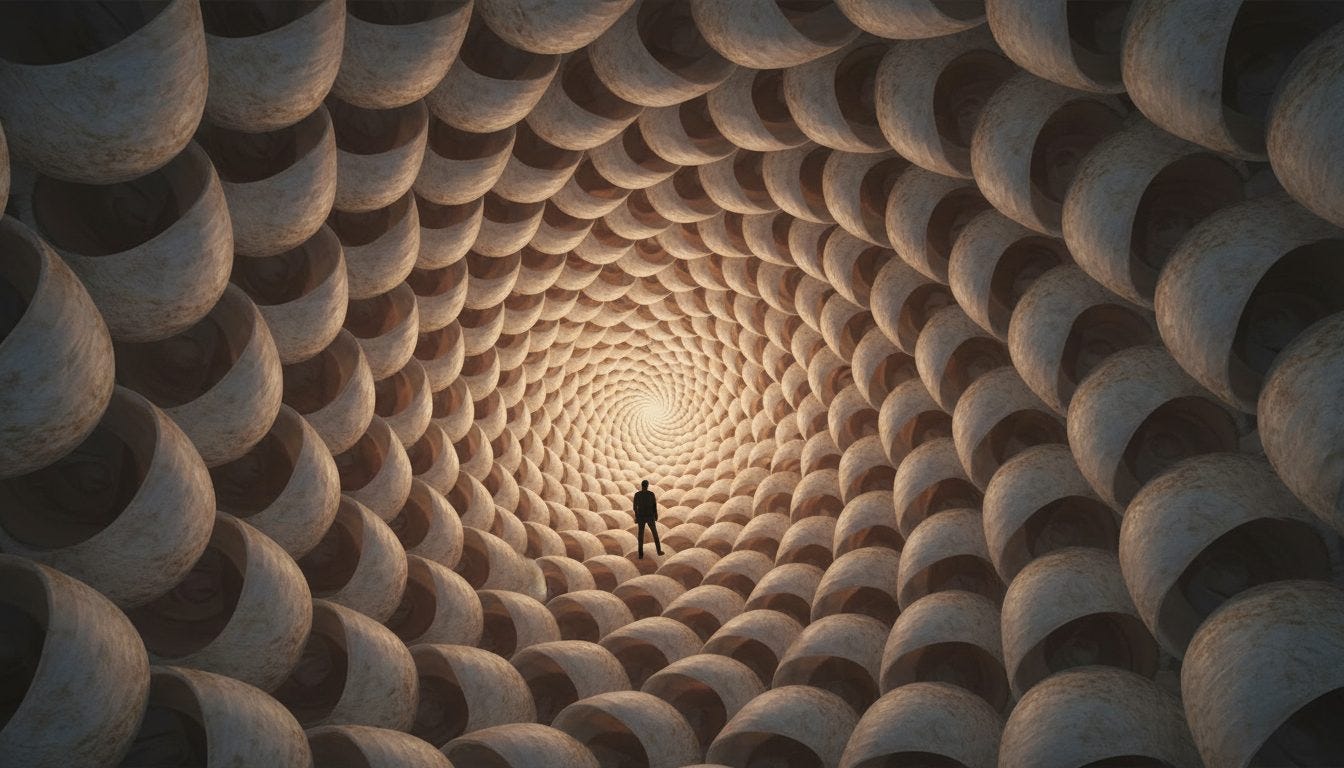

After signing, they guided me down a long corridor to a white room so brightly lit that not a single shadow existed. Embedded in the far wall was the spiral scanner. The cavity was so much like a snail’s shell that I thought I would hear the sound of the sea inside. I undressed and settled into a fetal position within the scanner. Coated in the sticky resin that lined the interior, I felt like a slug. In less than half an hour they took a mold of my body and transferred the memories from my brain to a neural box.

According to the doctors, I had five months left to live. Riviera would implant my replacement into the world in one hundred eighty-two days. When they woke him, they would explain that he was no longer sick. The genetics would be impeccable—a standard copy of the best version available at the moment. Everything would be fine. It wasn’t new.

Entire families scheduled their rebirths through Riviera’s panacea, promoted by the State, on a planet that scarcely had children anymore. They coordinated a future date, a new origin, and when the day arrived the story began again.

Everyone returned to live in the same house, or one very similar. Lost uncles knocked at the door, grandparents, parents—who had even ordered replacements for their children in case something happened to them. And those children, when they grew up, did not order new copies. They chose to return using the existing child version: the State, in its eagerness to recover childhood, subsidized the entire youth of those who came back aged eight or younger.

I had nothing to worry about. I hadn’t considered a single contingency. One morning when I woke, I looked in the bathroom mirror and no longer saw my usual pallor. Within a week I had regained all my strength. The new tests made it clear: I had nothing left. I was completely cured. If I was going to survive, I did not want to be replaced. And I was not willing to do something insane, as others might have: I was going to stay alive.

The first thing I did was call Riviera to cancel the procedure. They told me it was impossible, that I should read the contract. When I reread my copy I discovered a clause I had overlooked at signing. It stated that seventy-two hours after activation the replacement developed synaptic activity. At that moment it became an entity with rights. The process could not be stopped. And it was forbidden to keep the replacement in Riviera’s facilities beyond the scheduled implantation date.

In the days following my recovery, I regained a creative enthusiasm I thought I had lost forever. A dream inspired the idea for a novel in my favorite genre: frisson fiction. It started from a premise: that reality is a coherent hallucination created by our senses. If beings existed with different sensory organs, their world—their houses, their cities, their bridges—would be invisible to us, pure phantom architecture. My story followed an astronaut who arrived on an apparently empty planet, unaware that he was walking among the buildings of a transparent civilization.

I wrote the first chapters and felt the cerebral orgasmic rushes typical of the genre. I worked at dawn and sensed my mind ignite. It was as if a synaptic shepherd guided my neurons to a verdant field where a warm sun always hung overhead.

Suddenly I was certain I could sustain this creative explosion for many years. It would carry me into old age. I would die satisfied. I would need no one. Yet I had not forgotten her. I mean my ex-girlfriend.

With her I had known a loving stillness I hadn’t even realized existed. The relentless search for the meaning of life no longer mattered: I had found it in the peace of watching her sit on the floor, head tilted, long black hair falling over her face, absorbed in her work.

We spent our days working together. She designed living toys; I wrote the storylines for each character. The company didn’t pay much, but we did what we loved. Even though fewer and fewer children were born, every month many replacements arrived. At first we never stopped working. Our jobs depended on those kids playing.

We hadn’t foreseen that the returning children would stop playing. Suddenly they spent afternoons staring out their bedroom windows at the garden. Or they spoke—heads tilted—to an imaginary friend who seemed to be underground.

Eventually the living-toy company shut down. When that work collapsed, she sank into sadness that turned into depression and then anhedonia. One day she managed to get out of bed and called a taxi. Before getting in she pressed her lips to mine. It was a wet kiss that sucked out my soul and blew up the final wall between us. I understood that until that moment we had not been two. After that, I never saw her again.

The first few days I didn’t look for her. I even thought I had been the one to suggest we take a break. A month later I waited for her every day. And when I realized she wouldn’t return, life emptied of meaning. I stopped creating stories. Stopped reading. Until I fell ill. From then on I was no longer a sad man. I was a dying man. And that dying man needed someone else to keep waiting.

But now that creative momentum had saved me from nostalgia, I wanted to live more than ever. And I felt sorry for my replacement. When he woke and learned he was no longer sick, he would still wait for a woman who was never coming back. I had to prevent that new version from being implanted in the world.

Every day, before sitting down to write, I went to Riviera. I rode the elevator, walked identical corridors, knocked on door after door, all in vain. Whenever someone appeared they passed me to another employee. And that employee, already aware of my persistence from the others, usually reminded me there was no cancellation possible. The worst part was that it made sense: what were they going to do with that stored body? Burn it?

When the date arrived—the day I was no longer supposed to be in the world, but my double was—it wasn’t hard to find him. One afternoon, with clouds tinted pale orange, I headed to the house where I had learned he lived. It wasn’t far; I walked unhurriedly, as if I knew the way by heart.

The house was elegant but simple: single-story, almost identical to mine, though smaller. I was surprised by the absence of cats in the front garden. There was a dog behind the garage gate. It barked at me, then—as if recognizing me—celebrated with little hops, planting its front paws on the ground.

A dog? I had never liked them. One bit me when I was a child. Where were the cats my replacement was supposed to have? Had he not yet had time to adopt them? I saw a rat cross the main path.

I remembered the Chinese zodiac legend: during the race to the Jade Emperor’s palace, the rat pushed the cat into the water. The cat was left out of the twelve animals. That’s why cats hate rats and dislike water.

I knew that in that zodiac I was a Snake. My successor, however, should be a Monkey, based on the activation year. That reassured me a little, though I didn’t believe in astrology. If he liked dogs, perhaps he wasn’t so similar to me and had already forgotten her.

I approached the door and nearly knocked three hard times—only for the impulse to turn into three steps backward, then more, until I tripped over the protruding roots of an enormous ficus.

I was afraid to face the sad man I had been. And I forgot I had come to tell him my revelation—to save him—and that I had even thought we could write together, like twin brothers.

Hunched beneath the ficus branches, besieged by mosquitoes, I saw my replacement in the living room, sitting on a sofa, watching a newly released movie I didn’t recognize. He smiled sideways; something in the film struck him as implausible—surely, I would do the same thing. At that moment my own lips stretched. I couldn’t control them.

Then he turned his head and looked at me. Just for an instant. After that he returned to the screen as if nothing had happened. He must have known I hadn’t died. It didn’t seem important to him. To him, perhaps I was just an animal approaching his home in search of warmth.

There was no point hiding from myself. I sat at the foot of the tree and leaned my back against the trunk. I fell asleep. I dreamed I was curled inside the spiral scanner again. I tried to peel off the sticky resin enveloping my body. But there was no way to detach and escape. Then the abrupt braking of a car parking woke me.

In the glow of the streetlights I saw a short woman with long black hair run up the main path to the door. When she reached it she stopped, sighed deeply, smoothed her hair, and rang the bell. He opened the door and she rose onto her tiptoes to embrace him.

She looked younger than when she left me. The woman I had known no longer existed in this world. She had signed with Riviera without me knowing. Her replacement had come looking for me. But not for me—for him.

I understood that he no longer needed me. That his fate would not be creative solitude. And that he had just experienced a joy which, given the circumstances, I would never know. Suddenly the dog barked at me, as if it no longer recognized me.

I walked away slowly. There was no need to flee. No one was going to chase me. I wandered aimlessly and came across one of the new churches. The door was open. I entered, heart pounding, and sat on a pew.

I looked up at Christ on high. The android, on the metal cross, lifted its head from the wall. It offered me its gaze, full of sorrow and consolation. I lay down on that hard bench and crossed my arms over my chest, as if unwilling to surrender completely to reality.

Through the transparent dome I saw a rocket cross the sky. Then another. I touched my cheeks with my fingers. They were wet. I was crying. I didn’t know whether from joy or from pain.

Adrian Fares, 2026

Read this story in Spanish:

adrianfares.blog/un-contrato-conmigo-mismo-2026/

short stories

Index

previous short story: The Turning House

novels

Diary of a Broken Android

X: Thresholds

written by Adrian Fares

A great read, I was just glancing at me emails, but it reeled me in and I’m still there laid on a bench watching rockets in the sky 🚀

This is brilliant. Well written, yes. But, the fact that it doesn’t resolve cleanly is its real power. Well done!

Nice to find you. Subscribed.